It’s not just about how much you move—it’s about how you move throughout the day. New research suggests that the way we accumulate physical activity could be just as important as how much we get. Want to live longer? The pattern matters!

A fascinating study published in BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine by Yerramalla and colleagues brings some eye-opening insights into how our daily movement behaviors affect our mortality risk. The researchers tracked nearly 4,000 older adults (ages 60-83) for over eight years using wrist-worn accelerometers—those nifty little devices that measure your every move.

Beyond Step Counts: The Movement Profiles

Instead of just counting steps or minutes of exercise, the researchers looked at 13 different movement features spanning six dimensions: overall activity level, total duration, frequency, typical duration, activity intensity distribution, and timing of activity.

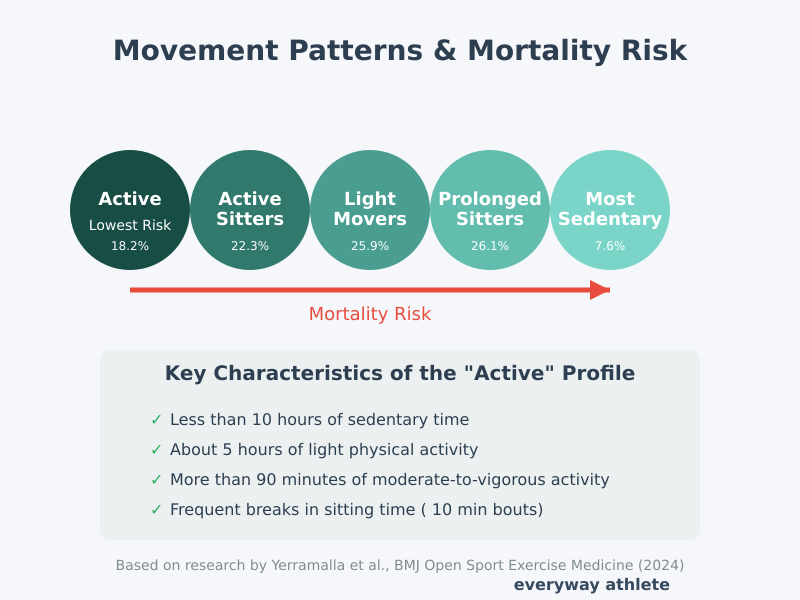

Using these features, they identified five distinct movement profiles:

“The Active” (18.2% of participants): These movers had the lowest amount of sedentary time with lots of breaks (shorter sitting bouts), plus the highest levels of both light activity and moderate-to-vigorous exercise.

“Active Sitters” (22.3%): Despite longer chunks of exercise and a well-distributed activity pattern, these folks still racked up significant sitting time.

“Light Movers” (25.9%): Less sedentary than some groups, with decent light activity but less moderate-to-vigorous exercise.

“Prolonged Sitters” (26.1%): The second-worst profile for sedentary behaviors, though they still moved more than the bottom group.

“Most Sedentary” (7.6%): The couch potatoes—longest sitting time with the fewest interruptions and minimal physical activity.

The Life-or-Death Difference

Here’s where it gets real. After adjusting for factors like age, sex, health conditions, and lifestyle habits, the researchers found a clear link between movement profiles and mortality risk:

- “Most Sedentary” group: 3.25 times higher risk of death compared to the “Active” group. Yikes!

- “Light Movers” group: 1.75 times higher risk

- “Prolonged Sitters” group: 1.67 times higher risk

- “Active Sitters” group: 1.57 times higher risk

The most surprising finding? The three middle profiles had similar mortality risks despite different movement patterns. This suggests that balance matters—focusing just on light activity or just on longer exercise bouts isn’t enough.

What This Means for You

The good news: approximately one-fifth of the older adults in this study had the healthiest “Active” profile, showing it’s absolutely achievable! This profile wasn’t just characterized by more exercise, but also by:

- Less than 10 hours of sedentary time daily

- Around 5 hours of light physical activity

- More than 90 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity

- Frequent breaks in sitting time (sedentary bouts averaging less than 10 minutes)

- Well-balanced distribution of activity intensities throughout the day

Current guidelines focus primarily on getting enough moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (150 minutes weekly). But this research suggests we should also pay attention to breaking up sitting time and getting more light activity throughout the day.

The Bottom Line

If you’re in the “Most Sedentary” profile (you know who you are!), don’t panic—the researchers specifically note that any improvement in physical activity and sedentary behavior might be beneficial for this group.

The key takeaway? Movement matters in multiple ways. It’s not just about hitting the gym for an hour—it’s about how you distribute activity across your entire day. Aim to:

- Reduce total sitting time

- Break up long sitting periods with movement snacks

- Get plenty of light activity throughout the day

- Still make time for that moderate-to-vigorous exercise

Remember, it’s the overall pattern that counts. So get up, shake it up, and mix it up—your future self will thank you!

Interested in reading the full study? Check out “Association between profiles of accelerometer-measured daily movement behaviour and mortality risk: a prospective cohort study of British older adults” by Yerramalla et al. in BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine (2024).